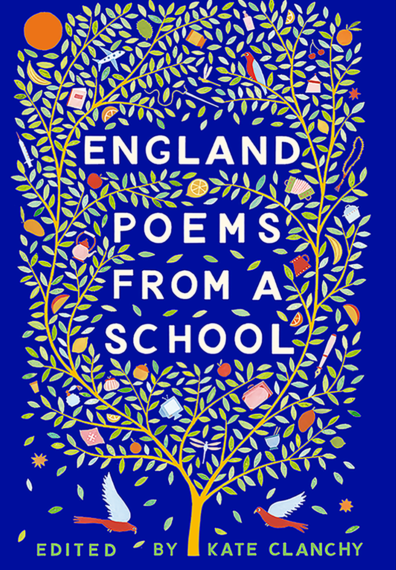

Kate Clanchy, ed., England: Poems from a School (Picador, 2018), 78pp, £9.99.

‘I want a poem,’ writes 18-year-old Shukria Rezaei in the opening pages of this anthology, ‘with the texture of a colander / on the pastry’, one that is ‘so rich / it leaves gleam on your fingertips’. Wry and insistent, her demand – for poetry that bears the imprint of a familiar elsewhere, while lending its voice to the everyday realities of suburban Britain – is answered in abundance by the 58 poems (and short prose vignettes) that follow; each a celebration and reminder of what ‘England’ means, through the memories and journeys of those who have chosen to call it home.

The 22 young writers are students of the poet and novelist Kate Clanchy at Oxford Spires Academy, and have arrived in the UK from countries as various as Bangladesh, Poland, and Syria. As Clanchy (also editor of this book) describes in her foreword, they belong to a school community that, by virtue of its sheer diversity, bears ‘a special sort of openness’: not only to the different languages, traditions and experiences that the students bring with them, but to the possibilities of their writing. Indeed, the Oxford Spires poets have won more prizes than those of any other school in England (no mean feat especially for those writing in their second language), and these poems are ‘charged with excitement because they are written as England changed, on the cutting edge of that change’.

For many, England is first an imagined country, before it is encountered fully in the first, bumpy hours of arrival. Rukiya Khatun captures this shifting perspective beautifully in her poem ‘England’, which lends the anthology its title. ‘I had seen it / in photographs’, she concedes, but photographs can only tell you so much. ‘Was the now searing sun ripe there? / Would the buds grow, / from season to season?’ When she eventually arrives, it is a coming of age: ‘I set out to be a woman, / fearless of the natives […] In that world. / Not mine’. At once bracing and distancing, her poem reminds us that settling in is never seamless, whether for those who have escaped ‘the claws of war’ (Azfa Awad, ‘War Memoir’), or even those who ‘cannot remember for sure / the soft of the snow in [their] country’ (Ftoun Abou Kerech, ‘The Doves of Damascus’). All must confront the ‘strange smell’ of someplace new, a second home where ‘the same / clouds appear, but nothing is the same’ (Rukiya again, in ‘Homesick’).

Faced with daunting change, these young writers have language on their side, as a shield and comfort, or simply as a way of approximating – and tempering – the unspeakable. 15-year-old Mukahang Limbu, for instance, records the violence and confusion of an attack on his family with these powerful opening lines: ‘And that day, just living / beat me up with its fluid limbs’. Each subsequent couplet begins with ‘And that day…’, as if revisiting the moment of trauma afresh, and further repetition deepens the effect as the poem thuds towards a haunting conclusion: ‘And that day I heard her. / I heard her, I heard her, / I hear her’. Aisha Borja, likewise, uses the cadences of the English language to great effect in capturing the unspoken weight of gendered expectations at home. Over the din of family conversation, we hear a grandmother’s nagging on loop: ‘suddenly / as if she had tapped a baton / on a sheet of music / it starts: Are you a girl? / Girl? Girl?’ (‘Not this year Grandma’). With great urgency, we are pulled into the space of each poem to find a singular experience rendered with heartbreaking clarity within.

Some pieces are brief and vivid sketches, while others make room for deeper reflection. Taken together, however, they offer a fitting portrait of modern England that is as painfully necessary as it is difficult to put down. This is not just because many of us, in privileged circles, would not encounter the slights and traumas described by these brave young poets (or as Azfa calls them, ‘the richness of my sorrows’) if not through their voices. It is also because the England of their imaginations – a country of ‘second chances, tolerance, kindness, and luck’, in Kate Clanchy’s hopeful words – can only take shape if we begin to imagine it too. Thankfully, they have given us the words to do just that.

Theophilus Kwek has published five volumes of poetry. He is co-editor of Oxford Poetry and The Kindling.