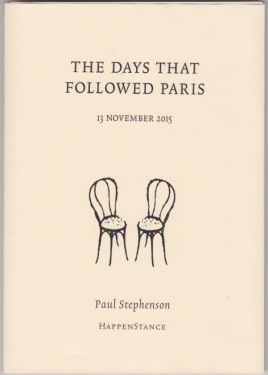

Paul Stephenson, The Days That Followed Paris (Happenstance, 2016).

How can we deal with a difficult present, respond to crisis? Crisis is everywhere and every day. We are enveloped in competing narratives of crisis, social constructions of incidents being ‘critical’, of events being so serious they are ‘critical junctures’ that will change the course of tomorrow. All around us, in the paper, on TV, on the radio, in social media’s many guises. Where to start?

First there are the big ethical questions. In November 2015, while living in Paris, I wondered if I should I write about the terrorist attacks? Did I have permission to do so? Was it right – or was it opportunistic, self-indulgent, in bad taste? After all, I was at home that Friday night and on the other bank of the river – the Left Bank, which was that night, by chance, the right bank to be on. I wasn’t harmed or injured, hadn’t died. I wasn’t out enjoying myself. I wasn’t affected. Or was I?

In the days that followed, the whole world was affected. Not least the city dwellers of Paris. This was evident when venturing out. Public spaces were closed. Parks were locked. Streets were empty. Heightened security. So much uncertainty. The trying to make sense of it all. In January 2016 I wrote to Helena Nelson at HappenStance, having looked at what I’d written with a little recul. By then I’d stopped writing. Anything new I attempted failed, felt unauthentic, because I no longer experienced that same incredible intensity of fear. As I wrote to Nell:

I talked to a few people over Christmas about the whole issue of writing about the attacks, and admitted I was hesitant. The general consensus from non-poets and poets alike is that we can only seek to interpret or record the public through the personal. We all experience these terrible events and strive to make individual sense of them. Much we experience through the news and social media, not to mention the atmosphere of the street. So it is valid to record this, and I should give myself permission.

I came across some interesting thoughts from Larkin too, in a chapter from a second-hand book I picked up from wonderful Berkeley Books here in Paris (Nine Contemporary Poets by P. R. King 1979). King says: ‘He [Larkin] has written of poetry as an act of preservation, a way of defeating time’:

I write poems to preserve things I have seen/thought/felt (if I may so indicate a composite and complex experience) both for myself and for others, though I feel that my prime responsibility is to the experience itself, which I am trying to keep from oblivion for its own sake. Why I should do this I have no idea, but I think the impulse to preserve lies at the bottom of all art. (H. Peschmann, ‘Philip Larkin: Laureate of the Common Man, English, 24 (Summer 1975), p. 51.

In November 2016, around the time that I launched my pamphlet of poems on the first anniversary of the attacks, I discovered the work of the late US poet C D Wright (1949-2016). Her poetry ‘projects’ made me consider the poetical strategies at our disposal and how we might attempt to combine the personal and societal/political, or rather, use the personal as a vehicle to tell the bigger picture.

~

This made me think retrospectively about the approach I had unconsciously taken with my Paris poems. Looking at C D Wright, who used a painterly approach to writing, using fragments and small pieces of text to layer a reality, create a lexical quilt of observation/sensation, I thought more about the distinction between the people that inhabit a place, the physicality of the location, and the encounters that take place. There are also script-like qualities to Wright’s work. It drove home to me the theatricality of the urban environment and the way in which those caught up in crisis are, inadvertently perhaps, the cast in a contemporary tragedy. Crisis is played out. There are settings, scenes, voices.

Looking back we can reflect, investigate, perhaps even provide answers to crisis episodes. But writing in the present we can’t hope for that, we don’t have the luxury of seeing retroactively. We can only observe, take note, bear witness to the now. And this witnessing inevitably means distinguishing between direct witness – with our own eyes and ears – and the indirect witness that we all are, experiencing crisis through the lens of the camera and television.

As such, the poet might well use living language as a source material, as I did with Facebook and Twitter, or use film and the moving image from YouTube to respond ekphrastically. One must be cautious, however, of the authenticity of such material.

To get close-up, the poet might also journey in person through the streets, to look and listen, take in the surroundings, see how the immediate environment is responding, coping, behaving. It was by venturing out that I was gradually able to reclaim the city. Witnessing how others were interpreting the crisis and carrying on, no doubt helped me to process what had occurred and find much-needed words at a time when words seemed impossible, futile even.

What To Say

Now everybody is saying something.

Somebody asks me to say something.

They ask me if I will write something.

I’m not sure, to be honest, what to say.

Everything seems to have been written.

I am not certain I have anything to say,

not convinced I want to say anything,

so for the time being decide not to.

Not for the moment, best wait and see

if something specific needs to be said.

Meanwhile, I keep listening, watching,

reading, what others have been saying,

to see if was something worth saying,

to see if something is still to be said;

anything, anything I should have said,

when it was me who was saying it.

Paul Stephenson grew up in Cambridge but recently spent 3 years living in Paris. His pamphlet ‘The Days that Followed Paris’ was published in November 2016 by HappenStance. His first pamphlet ‘Those People’ was published by Smith/Doorstop in 2015, having won the Poetry Business Book and Pamphlet competition, judged by Billy Collins. He studied modern languages and then European Studies, and took part on the Jerwood/Arvon mentoring scheme. He has a blog/diary at www.paulstep.com