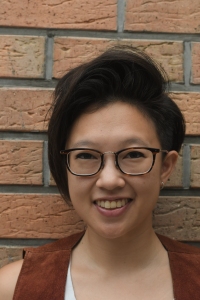

Topaz Winters – who describes herself as ‘a girl with raven hair and a sestina soul’ – is the founding editor of Half MysticPress, creator of the Love Lives Bot, and author of four books. Her most recent collection, Portrait of My Body as a Crime I’m Still Committing (2019), was a finalist in both the Broken River Prize and Gaudy Boy Poetry Book Prize.

This interview is adapted from a conversation between Winters and the poet Stephanie Dogfoot in May 2019, at the launch event for Portrait. It has been adapted and republished with their permission.

I want to ask you about the genesis of your book: what was the publishing process like? And also, it’s a self-published book – what made you decide to self-publish?

The publishing process for this book was tough. For those who don’t know, I have three previous books, of which two were published by presses. I always feel like kind of an asshole when I say this (laughs), but I actually had never been rejected by a publisher before I wrote this book. For the two books I published with presses, the first press I submitted to accepted them, so I didn’t really have an experience with that.

But with Portrait, I submitted to four or five publishers, got rejected, and was like, okay – it’s part of the process. Submitted to two or three more publishers, got rejected again, and thought, oh dear, maybe there are some problems. And then… I started winning awards for the book! It was actually shortlisted for two amazing awards, which I was really grateful for. So there was this interesting conundrum around the book, where on one hand it was getting rejected everywhere, but on the other hand, people who ran prizes clearly liked it enough.

Finally, after about seventeen or eighteen rejections, the question was, what do we do now. I think self-publishing would have been the next obvious step. But I didn’t really want to self-publish, and I didn’t know why. Self-publishing would make sense logistically, and business-wise… but what I realized was that I didn’t want to self-publish because I felt that would be admitting defeat. Or admitting that no press actually wanted to publish this book, and therefore it wasn’t good enough, and so I had to do it myself.

‘That’s not a good enough reason. I’m not here to put my ego over my art.’

And I decided, that’s just not a good enough reason. I’m not here to put my ego over my art. At that point I realized that continuing to pitch this book around would have been more about my pride, than about believing that I would find a perfect home for this book in, say, the nineteenth press. So yeah, I’m self-publishing because I thought it was really important to break through my own ego, because I can’t put that above my art. I can’t allow myself to do that…even sub-consciously.

Thank you for that. That’s really something that a lot of young writers or artists struggle with: your vision versus your art, and publicity and accolades and people liking or reading your stuff. But yeah, I think it was a really brave thing to self-publish – plus you have total control over your work, which is really cool.

On that note, what would you say was the hardest part? You talked about a lot of challenges, which is really interesting to hear, because not enough people talk about this when it comes to publishing. What do you think was the hardest bit of this whole publishing process?

Self-publishing was a big thing, in itself. But other than that, I think just putting together the poems in this collection, which in many instances deal with topics I’ve never talked about before, either in my previous books or on my blog, or really anywhere publicly.

You know, there are poems in this book about food, and the body, and my very darkest moments. It was tough to give myself permission to make those public, because I wanted to put out a book that was personal, but also a book that was good, craft-wise. The challenge was balancing those two things, and ensuring that even when I wrote a horribly personal poem, I wouldn’t add it to the collection because it was so personal, but because it was actually a good poem.

Wow. How many poems did you not include?

So many! (laughs)

One last question about the process: what kind of advice would you have for first-time young poets – many of whom are here – about publishing a book for the first time? Coming from someone who has published several times?

Finish your shit. Do it. So many people tell me about this amazing book they’re writing, and they really want to publish it, and I ask them if they’re done with it, and they say – no, I’m three chapters in, or I’ve only written ten poems. It’s wonderful to want to publish, and publishing is the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done with my life, but you need to finish what you start.

‘Finish your shit. Do it […] You need to finish what you start.’

There is no book if the book is not finished. But I get it, right? Especially for us as young people, we have short attention spans – we want to chase shiny new things. I get that completely. At the same time, in order to put a book into the world that is carefully crafted and curated, and really represents the person you are at a specific moment to the best of your ability, you must finish it.

I definitely have struggled with this, and a lot of it is just… not choosing perfection, in the way many of us tend to do when we’re young, and not believing that it is possible to put out a perfect first book. Because that is what paralyses so many of us; that is what makes us say, if it can’t be perfect, I don’t want to finish at all. But once you finish your work, you have something, and that’s where the magic happens.

Okay. Moving on to the content of your book – one thing I feel when I read your poems is a real sense of urgency. Where do you think this comes from, and what makes your writing urgent?

Yeah, I think so. (laughs) I think I would characterise my work as urgent, mostly because when I write I’m trying to capture a singular moment, rather than an overarching scenario, or the entirety of a feeling – I’m trying to describe what happens in a single second, a single minute, a single hour.

And I think there is a sense of urgency in knowing that, of course I write after the fact, so I will never be able to capture something as accurately as I lived it. But I want each of my pieces to remind me of a time when I felt something very deeply. And I think that feeling deeply does translate into urgency. Because it’s so hard to stay faithful to a moment. And writing a poem is attempting to be faithful to a moment, and that is just the hardest thing. (audience applauds)

Queerness, and in particular bisexuality, is an important part of your writing. As a queer person, for me, it was something that inspired me to write poetry, because I felt there was not enough queer literature out there, and not from Singapore especially. Do you think queerness is something that pushed you to write, and why do you think it’s an important part of your work?

I think love pushes me to write. And by virtue of being queer, it becomes a queer poem. What I want to do is write a poem where I’m kissing a girl, and not have that be a radical political act. And not have that be an act of rebellion or revolution. Unfortunately, in the country we live in, that’s not always the case. So like I said: I write about moments, and about the times where I felt most in love with myself, and with the world, and with another person.

‘I want to [write] a poem where I’m kissing a girl, and not have that be a radical political act.’

When I think about the ways in which love is expressed, they come with a lot of social baggage. And I don’t want my poems to be categorised as queer poems, but on the other hand I’m very grateful that they are. Because frankly I don’t think we should need a category of queer poems, but in the world that we live in right now, it’s important for us queer folk to find each other. And only by creating this work, and writing about happy queer people, and sad queer people, and angry queer people – and understanding that it’s such a spectrum, none of it is singular – I think that is how we make it so that it’s not a political statement anymore. And that’s what I’m working towards.

So it’s about normalising queerness as a valid form of love.

Yes.

Mental illness is another big part of your work. How do you deal with being so vulnerable and open about a topic that so many people in Singapore are terrified to even address, or confront?

It’s tough. When I was younger, I was definitely a lot more open about it, especially online, on my blog and social media. That was because I didn’t have that big of an audience, or any audience at all – I knew the writing was public, but it didn’t feel like anyone was really reading it?

These days it’s a little harder, because I know that when I put something into the world, someone is going to be affected by it, for better or for worse. I try to sit on my poems that deal with mental illness, so that I am able to capture that moment in the piece, and then maybe later when I’m a little more stable, I’m able to go back to it and see – is this something that should be out in the world? Because writing is catharsis, and that can be deeply valuable, but it’s not always valuable to share.

With this book I tried to put out the most intimate, the most vulnerable moments. Because I do think those dark times need to be written and published about. At the same time the fact that they’re in a book, and not on a blog for the whole world to see: that’s a bit of a comfort to me, that provides a bit of a barrier, where the work that I’m publishing right now feels not as immediate. It feels less like people are investigating or picking away at me, the way it felt when I was younger.

One of my favourite poems in this book, and probably also the one with my favourite title, is ‘New York City Probably Has An Anxiety Disorder’. (Audience laughs) One of the things I realized about the poems in your book is that they are all very atmospheric; place is very important in them though you don’t always mention place-names. Why did you decide to name New York City in this poem? What role do places play in your writing, and to what extent are you inspired by places that you’ve lived in – since you’ve lived in several throughout your life?

I think place plays a huge part in my writing, though it’s not something I fully understood till a few years ago. I decided to name New York City because I adore New York City with my entire heart, but it also makes me incredibly anxious. New York is a place that feels deeply human to me, a place that feels so vibrant, and strong-willed, and stubborn. It’s also a place that feels incredibly scared. That is something – in that particular poem, and the book as a whole – that really characterises a lot of the places that show up in my work, the dichotomy between anxiety, fear and insecurity, but also the utter joy of living and being human.

‘I adore New York City with my entire heart.’

New York City is the most human place I know. So sharing that, specifically by name, was almost a way of spreading that joy. Obviously not all my poems are based in New York City, but I hope all of them evoke that same kind of contradiction.

Let’s move on to the more esoteric question of intent. Who do you write for, and who would you say this book is for?

I write for myself, which makes me the most selfish poet in the world. But yes. It’s hard for me to take responsibility for people who read my work and feel things about it. Obviously, I’m so grateful that people are moved by my work, if they are. I write to capture a snapshot of a specific moment in my life, and I hope that people are able to find some of their own truths inside of it. But first and foremost, I write because it’s the only thing I’ve ever really known how to do, and it’s the only thing that helps me to make sense of the world. If people enjoy it that’s a bonus, but it’s not at the forefront of my mind whenever I’m creating.

What do you want people to come away with after reading this book?

I want people to come away with the knowledge that there is darkness everywhere, but equally, there is light everywhere. What I realized when writing this book was that in my darkest moments, there was still a sense of hope. This book has taught me that there are always two sides to every moment, to every story that I live and every story that I tell. And so I hope that nothing about this book feels simple. I hope that all of it invokes something very complex and maybe unnameable, and I think if it’s done that, then it’s done its job.

Thank you. Thank you. For my final question – what do you think is the most important thing that poetry should do?

Um, I’m nineteen – can we just make that clear? (Audience laughs) Gosh. I think that poetry should be candles, and poetry should be a fire, and it should be a compass… and poetry should rewrite and invoke and provide a soft place to land, it should make you hungry, it should make you hopeless, and it should give you all the hope you’ve ever had. I’ve always subscribed to the belief that poetry should comfort the disturbed, and disturb the comfortable. I think that’s probably the main thing.

~

Topaz Winters is an internationally award-winning poet, critically-acclaimed actress, & creative director at Half Mystic Press. She writes free weekly love letters to thousands of readers at topazwinters.com.